US military is quietly spreading the pandemic in the Pacific

US military bases are hotspots for more than just COVID-19 transmission, they also make island territories targets for climate disasters

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this article was printed in Common Dreams on Sept. 12, 2020, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 License. This article has been updated and revised by the author for republication.

Guam has always been the U.S. military’s best kept secret. Military secrecy isn’t really new, but in the midst of the global pandemic the Pentagon ordered bases to stop publicly announcing their COVID-19 cases. To date, 44,529 military personnel have contracted the coronavirus, and this summer military and public health officials declared the U.S. military a source of transmission both domestically and abroad. COVID-19 continues surging in the military, but that has not stopped its operations, which continue spreading the virus throughout America’s empire of bases—especially in the Pacific.

Guåhan—the indigenous name for Guam—is the hardest hit place in the Pacific region by the COVID-19 outbreak, and military transmission is clear. On April 1, the Navy announced it would offload 4,000 sailors from the coronavirus infected aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt to be housed in Guam hotels, drawing protests from local politicians and community members. Approximately 1,200 crewmembers were infected, resulting in the death of one sailor and many others contracting the virus for a second time or breaking the island’s quarantine restrictions during the months the Roosevelt occupied Guåhan.

Despite the outbreak, by early June, Navy leaders designated Naval Base Guam as one of its “safe haven” ports for deployed military ships to stop and enjoy free time on the island during the pandemic. This decision subjected Guåhan to an onslaught of visits in the months of June and July. Seven different ships—including the USS Nimitz, which had previously experienced a COVID-19 outbreak—docked to allow crewmembers to relax, supposedly without risking exposure to the island’s population.

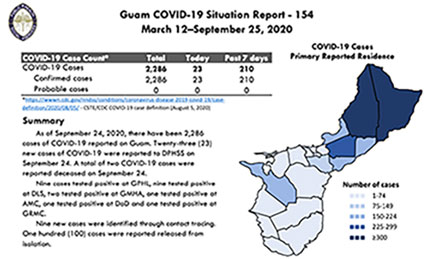

But the island’s COVID-19 cases continued to surge throughout the summer. By late June a surge in coronavirus cases among 35 airmen who tested positive in less than two weeks at Andersen Airforce Base prompted an investigation and the release of a list of 30 establishments visited by the infected airmen. On Aug. 20, the island’s COVID-19 cases prompted Guam Gov. Lou Leon Guerrero to issue a second more restrictive lockdown. Days later, another aircraft carrier, USS Ronald Reagan, arrived for its “safe haven” port visit. The day after leaving Guåhan, a COVID-19 outbreak was identified among the Reagan’s crew—the second outbreak that aircraft carrier has experienced this year. The Navy confirms only that an unspecified “small number” of positive cases were identified. To date, COVID-19 has infected nearly 2% of the island’s population of 165,000, putting the military on island in health condition “Charlie.”

Though Guam’s military still is following Pentagon restrictions on reporting—the USS Theodore Roosevelt situation has meant that the local Guam government is separating out military cases in their COVID-19 data for the island. From the Naval ships that visit for “safe haven” to the airmen that flout public health protection measures, infections in Guåhan are tied to the military presence.

The U.S. military will continue to put the people of Guåhan at risk long after the pandemic ends, without a fundamental dismantling of the colonial project. After all, the military has always been a hotspot for colonial violence, destroying environments and occupying Pacific Island territories with impunity for generations. Despite the irreversible damage and desecration it inflicts, the general public is largely ignorant of its operations.

Politically, Guåhan is an “unincorporated territory,” a designation unilaterally imposed after the U.S. engaged in bombing campaigns and land grabs to recapture the island from Japan in World War II—in short, a 21st century colony. This place may just be the best kept secret that the U.S. has—a nearly forgotten island in Micronesia where the military conducts training and testing that it would never have attempted in the contiguous states.

In 2020, the military continues to occupy nearly one-third of this westernmost U.S. territory in the Pacific. Andersen Air Force Base and Naval Base Guam are two major military bases that host bombers, serve as a home port to nuclear-powered fast attack submarines, maintain huge munitions and fuel storage facilities, maintain a helicopter squadron, operate a Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) ballistic missile interceptor, and provide U.S. security forces to support the Department of Defense’s military strategy in the Asia-Pacific region. The U.S. is also implementing plans to further inundate the island’s existing military troop presence by relocating an additional 5,000 U.S. Marines from Okinawa to Guam. These elements of militarism are largely normalized as ensuring security and protection, yet research reveals that it is the U.S. military presence that makes the island a target for attacks and threats ranging from missiles to climate change.

As the largest global force, the U.S. military is the single biggest consumer of fossil fuels, largest producer of greenhouse gases, and single entity most responsible for destabilizing the Earth’s climate. The Department of Defense is the greatest polluter worldwide, with a continuous record of destroying environments and generating massive amounts of hazardous waste for its routine operations. Military expansion, as well as the operation of bases, exacerbates our shared climate emergency. Dispossession and environmental destruction from militarization demonstrates the overwhelming costs of U.S. empire—particularly among indigenous communities throughout the Pacific and Indian country. Among the legacy of violence is racism, which existed long before Senate panel efforts to remove confederate namesakes from military bases.

While threats from militarism and climate vulnerability are woven into everyday life in a U.S. colony, this situation has also been met with centuries of continuous resistance. With a ceaseless movement for self-determination, Guåhan and its indigenous Chamoru people continue to challenge the narrative that the island and its surrounding waters are merely a strategic military base for the U.S. to destroy with its Pacific bombing ranges.

As Chamoru scholar Dr. Kenneth Gofigan Kuper explains, living “at the tip of the American military’s spear” means living with militarization that is “responsible for environmental contamination, with toxic chemicals and heavy metals sludging through the island’s arteries.” And though the country is quickly approaching the U.S. presidential election in November, Guåhan has “no vote in the electoral college, no representation in the U.S. Senate, only non-voting representation in the House of Representatives, and are under the ‘plenary’—or complete—power of Congress.”

While civic engagement and voting rights are important, U.S. colonization and militarization are constant threats to political power for the people of Guåhan. Until the island exercises its inherent right to self-determination and the island chooses its own political future, decisions on everything from public health to climate action and the economy will be continuously deferred to external powers. The impacts of these injustices are clear in the midst of surging COVID-19 cases and deaths as the military continues its construction of a live-fire training range on sacred land in Guåhan and executes war games throughout the Pacific—like the biennial Valiant Shield in the Marianas and RIMPAC in Hawai’i.

Though Guåhan floats on the other side of the world, every sector of civil society—from pension funds and university endowments to state and local municipalities—is implicated in the military war machine. Public and private assets are entangled with military contractors, weapons manufacturers, and war. Such profiteering is largely normalized today. From public to private assets, every part of the “American” experience has profited from colonial control in the Pacific. Yet divesting these dollars from destructive weapons and war could mean reinvesting in what the pandemic has revealed we all so desperately need—genuine security in public health, education, housing, food, green jobs and a just transition from fossil fuels. As the protests against anti-Black racism continue in cities like Kenosha, Portland, Oakland, Chicago and Philadelphia—rethinking and defunding the police also means divesting from the military industry that structures all our lives.

Centuries of continuous colonization are not Guåhan’s defining story, and neither is the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated by the U.S. military’s exceptionalism. The people of Guåhan deserve even more than a symbolic change to military base names—they deserve an end to colonial violence.

Tiara R. Na’Puti (Special to the Saipan Tribune)

Tiara R. Na’puti is a Chamoru (familian Robat & Kaderon) scholar. She is an assistant professor in the Department of Communication and an executive board member for the Center for Native American and Indigenous Studies at the University of Colorado Boulder.