How Coca-Cola came to be in the Marianas

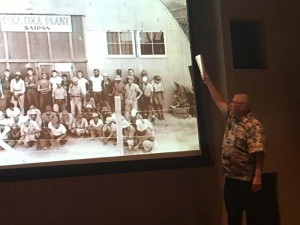

Steven Connor points to the original quonset that used to bottle Coca-Cola on Saipan. Posing in front of the structure are American GIs and embarrassed Japanese prisoners of war believed to be conscripted to help set up the structure. (Mark Rabago)

You can say that Islands Bottling Co. predated Imperial Pacific International, Ltd. as an investor from Macau and Hong Kong who took advantage of the economic opportunities in the Marianas.

Steven R. Connor, Mariana Stamp and Coin Club founder, discussed the intricate history of Coca-Cola in the Marianas—Saipan and Guam—during an over hour-long presentation last Jan. 20 at the American Memorial Park visitors center theater.

His research about the world’s No. 1 soda brand’s history in the Marianas came under a grant from the Northern Marianas Humanities Council.

Connor traced the origin of Coca-Cola in the Marianas to Charles Butler of Forth Worth, Texas.

A Navy man, he was sent to Guam in 1913 to work in the U.S. Navy printing office.

Butler used to work for a bottling plant in Texas. Some years after settling in the U.S. territory, he started to brew his own ginger ale, root beer, and bottled seltzer in his bottling plant.

In 1929, he got a license to bottle Coca-Cola in Guam and in the late 1930s opened a spanking new bottling plant in Agana. Then World War II came to the islands and he was promptly whisked to Japan as a POW, part of 500 U.S. citizens in Guam forcibly taken to Japan.

Connor said that with Butler out of the way, a Japanese officer wanted his wife, Ignacia, to bottle Coca-Cola for them. When she refused, they used the couple’s sprawling ranch home as the Imperial Army’s headquarters in Guam.

Liberation came to Guam and one of the casualties was the Butlers’ bottling plant in Agana—a victim of bombs dropped from the B-29 Superfortresses.

The Navy’s Seabees quickly reconstructed the remnants of the pulverized bottling plant, but Butler didn’t immediately get back his bottling plant, as the military wanted him to sell them the plant.

He refused and sued them and eventually had an out-of-court settlement. Butler continued to bottle Coca-Cola until he died of pancreatic cancer in the 1950s.

Connor said Butler’s widow and children continued the family business and renamed it to Guam Bottling Co. in 1964. Hong Kong businessman James Lee then bought them out in the 1970s.

Connor said Lee put in charge Carlos Taitano as president of the Coca-Cola bottling plant in Guam and, according to him, “the first thing he did was run this thing to the ground.”

Coca-Cola Corp. in fact sued Guam Bottling Co. for unsanitary conditions in 1975. A year later, Mother Nature changed the company’s fortunes in a big way.

“In 1976, Typhoon Pamela came and destroyed the plant and that was it. No more bottling of Coca-Cola in Guam has ever occurred since then,” said Connor.

In 1978, Lee filed for bankruptcy after Typhoon Pamela and Conner said the bankruptcy judge assigned the Coca-Cola license to Dutch company Foremost, which now runs Coca-Cola operations in both Guam and the CNMI.

On Saipan, Connor said there were originally two bottling plants set up by the Americans after World War II—one along Quartermaster Road and another in Lower Base where Cargo Express now stands.

In 1966, Taitano of the Guam Bottling fame decided to take over the bottling plant in Lower Base.

The Saipan operation was renamed Bottling Company of Micronesia and it became the hub of Coca-Cola bottling production in Micronesia during the Trust Territory days, said Connor.

From the get-go, Taitano’s venture was fraught with challenges. Connor said gecko eggs always found its way in the bottles of Coca-Cola despite the many processes they did to sanitize them.

Water they used to make the soda was also very salty and there was the issue of getting back the soda bottles they were making from scratch here on island.

Locals just won’t return bottles to get them refilled. They were also used to erect makeshift electric lines. Some were also filled with black powder and used as dynamite to blow up fish, aptly named bottle bombs.

Taitano wouldn’t have to wait long to divest himself of the Saipan bottling plant, though.

From 1966 to 1975, two critical events were percolating in China—the Cultural Revolution and the open door policy espoused by the administration of President Richard M. Nixon.

Connor said the Cultural Revolution nationalized all bottling companies in China and this prompted bottling companies to move to Macau and Hong Kong, at the time colonies of Portugal and the United Kingdom, respectively.

In 1972, Nixon’s open door policy encouraged foreign companies to invest in the U.S. and, heeding the call, Macau-based Island Bottling Co. purchased the Coca-Cola bottling plant on Saipan in the mid-‘70s.

One of the objectives of the Humanities Council-funded study was to see how America’s economic policies gave opportunities to foreign companies to invest in the CNMI and Conner believes Island Bottling Co., under the leadership of Timothy Lee Po Tin, proved that.

Partnering with the now Joeten Group of Companies and Saipan Stevedore Co., Island Bottling Co. secured a $1-million, 40-year lease to build a warehouse along Middle Road, where the Coca-Cola distribution plant now stands.

Connor said Lee’s company bought the Coca-Cola operations on Saipan with the intent of making it a distribution center for its canned soft drinks for Micronesia.

“[They] wanted to make Saipan a can distribution center and not continue bottling plant because maintenance of World War II-era equipment was getting expensive.”

Island Bottling Co. eventually changed its name to Coca-Cola Beverage Company of Micronesia and gave up bottling altogether in 1995.

Connor said fast-forward to 2017 and Imperial Pacific with its integrated casino resort plans is reaping the same benefits Lee’s Coca-Cola Beverage Company envisioned some 40 years ago.

“[This was the] time before Imperial Pacific and Coca-Cola Beverage went on to diversify and opened up Subway, Scoops, and Glimpses [Advertising],” he said.

Connor said Lee’s Coca-Cola Beverage Company was also responsible for bringing in the giant 500-lb concrete soda bottles used to advertise Coke, Sprite, and Fanta that once a upon a time littered the Saipan and Tinian landscape.

He likened the statues to modern latte stones and enjoined the public to help preserve these “cultural” icons. Of the original 20, only seven remain on Saipan and one Tinian.

“Three have been destroyed and within five years they will all be gone—gone pretty soon without any kind of preservation.”

Connor tried his best to preserve the giant soda bottles and even volunteered to foot the bill in one restoration project.

“The Zoning Office…consider these signs out of compliance. They said you have to maintain it and make it not look ugly. The cost for these bottle signs to come into compliance is $35 each.”

He was told, through the Zoning Office, that the local Coca-Cola office seems to prefer to take them all down rather than spend the money to restore them.

Connor said the history of Coca-Cola in the Marianas, especially Lee’s Island Bottling’s venture to Saipan, is linked to the the boom in tourism arrivals from China it currently enjoys.

“I wants to show tourists from China the connection with America’s brand of democracy and open economy that gave foreign investors originally from China economic opportunities ever since the mid-1970s,” he said.