Aug. 9, 1945: The decisive mission

North Field, Tinian. This photo by Leon Smith, 509th Composite Group, shows not only the atomic bomb loading pits but also the “high tech area” where subassemblies for the bomb were completed (just to the left of the 509th B-29s, as well as the three assembly buildings just to the northwest. (Leon Smith)

Tuesday morning, Aug. 7, 1945; the skies around Tinian were filled with ominous thunderheads. An early flight from Hawaii brought copies of the Honolulu Star Bulletin with the headline: Single Atomic Bomb Shakes Japan…” With no surrender message from Japan, the Project Alberta team continued to assemble the plutonium bomb nicknamed Fat Man, scheduled for dropping on Aug. 11.

That morning, Tibbets and members of his crew flew to Guam for a meeting with LeMay. Unfortunately, LeMay’s weathermen in China reported there was no guarantee of clear weather after Aug. 9. Because some of the newest parts for the plutonium bomb had not yet been tested, Dr. Ramsey stated, “that Project A would try to be ready for 9 August provided that it was understood by all concerned that the advancement of the date by two fill days introduced a large measure of uncertainty…”

Soviet leader Joseph Stalin went into a fit of depression after hearing about Hiroshima. Later, when he realized that Japan had not offered to surrender, Stalin ordered his armies to attack Japanese troops in Manchuria immediately, with a goal of landing troops in Hokkaido, northernmost of the Japanese home islands, before Japan surrendered.

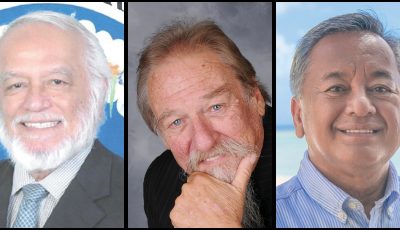

The Tinian chiefs of staff: From right, Rear Adm. Willian Purnell, USN; Brig. Gen. Thomas Farrell, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; Col. Paul Tibbets, U.S. Army Air Force; and Capt. William Parsons, USN. (Contributed Photo)

The next day, Aug. 8, the assembly team completed its work on Fat Man. It was towed to the loading pits and lifted into the belly of Bockscar, the strike aircraft. By early morning Aug. 9, the wind had shifted to westerly and a drizzling rain had set in. Iwo Jima could not be used for the rendezvous because of bad weather. The new rendezvous site was a little island off the south end of Japan called Yakushima. Tibbets’ navigator, Dutch Van Kirk, warned that they would never make the rendezvous.

The Bockscar crew arrived at their aircraft at about 01:00 to begin the pre-flight checks. When Ma. Charles Sweeney, the mission commander, fired up Bockscar at 03:30am, the flight engineer, MSgt. John D. Kuharek, discovered that the fuel transfer pump from the auxiliary tanks to the main tanks would not work. Sweeney shut down the aircraft and the crew climbed out. After consultation with Tibbets and Purnell, everyone climbed back on board and restarted Bockscar. With turbulence heavy on the way north, Sweeney was forced to fly at a higher altitude, burning more fuel.

Unknown to Sweeney or anyone on Tinian, Russian troops crossed the border into Manchuria at 12:58am Manchurian time, 05:58am Tinian time. The Soviet Union had joined the war against Japan.

Sweeney arrived at Yakushima just after 09am, Aug. 9, Tinian time. Five minutes later, Fred Bock showed up in The Great Artist with the blast measurement devices. James Hopkins, carrying the photographic equipment, did not show. Sweeney flew in circles waiting for him. At 09: 50 Sweeney gave up and headed for Kokura, their primary target, without Hopkins. They had already burned so much fuel that a return to Tinian was out of the question.

Bockscar. (Contributed Photo)

Arriving at Kokura, Sweeney found the city covered with haze and smoke. Instead of flying directly to the secondary target, Nagasaki, Sweeney decided to circle Kokura and come in from a different angle. When that failed to find a hole in the clouds, he made another pass. With another 45 minutes of fuel burned, Kuharek advised Sweeney that returning to Iwo Jima was also now out of the question. Sweeney headed for Nagasaki, knowing they had only enough fuel to make one pass, then attempt to land at Okinawa, which only had a runway long enough for B-24s. The mission was in jeopardy, as were their lives.

Standing in the cabin of Bockscar behind Sweeney was Commander Dick Ashworth, the Fat Man weaponeer. Sweeney tried to assure Ashworth that they could drop the bomb by radar. Ashworth, an Annapolis “by-the-books” naval aviator, said no. Orders were orders. If they could not see the target, they would have to jettison the bomb into the ocean or try to land with it at Okinawa. Finally, Ashworth agreed to make a radar approach and hope they could find a hole in the clouds, if Nagasaki was overcast. If not, they would drop the bomb by radar.

With “Murphy’s Law” ruling the day, Sweeney found Nagasaki covered with smoke and haze, and began the radar approach. Bombardier Kermit Beahan kept his eyes glued to his bomb site. At the last minute, he saw an opening in the clouds. He recognized the race track at the Nagasaki Athletic Stadium and shouted “I can see it: I’ve got it!” He made final adjustments and let Fat Man fall. “Bombs away!” Then corrected himself, “Bomb away!”

Fat Man exploded at 1,650 feet above Nagasaki at 12:02pm, Tinian time.

Fat Man being loaded into Bockscar. (National Archives Record Group 77)

Sweeney put Bockscar into the same tight, diving right-hand turn as had Tibbets, racing away from the blast.

With only three hours of fuel left and a three-hour flight to Okinawa, the crew began preparations for ditching at sea. Sweeney milked every mile out of his remaining, arriving at Okinawa after 1:30pm. Unfortunately, the Yontan airport had not received any notification of a potential B-29 landing and could not hear Sweeney’s plea for clearance to land. He had the crew fire all the flares on board and made his run at the landing strip, coming in high and hot. Just before touchdown, one engine ran out of gas, causing Bockscar to veer toward a line of parked B-24s. Sweeney regained control, just to have another engine die from fuel starvation just after touchdown. Had it not been for their reversible propellers to help them stop, they would have gone over the cliff at the end of the short runway.

After taking on half a tank of gas and eating Spam sandwiches, Bockscar took off for Tinian, arriving home at 11:06pm.

There were no Klieg lights on North Field, no dignitaries. They were treated to cold leftovers and medicinal alcohol after the debriefing.

At 06:45am, Friday, Aug. 10, 1945, Tokyo time, the Japanese government transmitted its initial offer to surrender to the Swiss and Swedish embassies to be relayed to the Allied heads of state. The Nagasaki mission, even with all its problems, became “the decisive mission” for the 509th Bombardment Group.

Don Farrell (Special to the Saipan Tribune)

Don Farrell is author of the acclaimed book Tinian and The Bomb, available on line at https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07BMTVF1K