Aug. 6, 1945: The milk run to Hiroshima

The aerial view of Hiroshima shows the A.P., the aiming point. Those that made the target map did not know that the A.P. was the Dr. Shima Clinic. (Contributed Photo)

At 04:15 Sunday morning, Aug. 5, 1945, Gen. Curtis LeMay, now deputy commander, U.S. Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific, received an updated weather report from China. The skies would not be clear over southern Japan until Aug. 6. The first atomic mission was to proceed.

Capt. Tom Hill, USN, Admiral Nimitz’ liaison officer to the Manhattan Project, passed the order to Col. Elmer E. Kirkpatrick, Jr., the Manhattan Project liaison officer on Tinian, who notified Capt. William S. “Deak” Parsons, USN, commander, Project Alberta, the team he had organized at Los Alamos to assemble and load atomic bombs in the field. The final assembly and loading of Little Boy, the uranium-based atomic bomb, was set in motion.

Although the Japanese knew that their war was lost, the Japanese military leadership, unwilling to accept their defeat, pressed every Japanese to commit, in effect, national “seppuku,” or ritual suicide. Thousands of men, women and children, American, British, Japanese, and Chinese, continued to die.

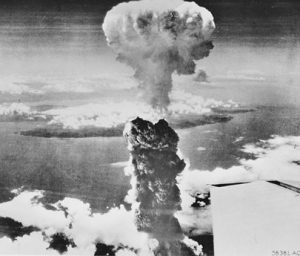

The aerial view of Hiroshima in the aftermath of the nuclear bomb explosion. Photo courtesy of the Atomic Energy Commission. (Atomic Energy Commission)

Inside Assembly Building No. 1, Dr. Edward Doll inserted the final critical parts into Little Boy number L-11. The bomb was trailered one-half mile to the loading pit, where a specialized team loaded it into Enola Gay. The plane was then towed to a hardstand where a double guard was set around it for the night.

Capt. Parsons became concerned that should Enola Gay crash on takeoff, the bomb could go nuclear and destroy half of Tinian, including the entire Manhattan Project team. In conversation with Rear Adm. William R. Purnell, member, the President’s Military Policy Committee, and Brig. Gen. Thomas F. Farrell, deputy director of the Manhattan Project, Parsons decided to arm the bomb after Enola Gay had taken off. Both Purnell and Farrell agreed.

The mission crews, led by Col. Tibbets in Enola Gay carrying Little Boy, Ma. Charles Sweeney in The Great Artiste carrying the blast measurement equipment, and Capt. George Marquart in Necessary Evil carrying the photographic equipment, arrived at their aircraft at about 0100 on the morning of Aug. 6, 1945. The Enola Gay was flooded by klieg lights. Video cameras were rolling and still cameras snapping. Tibbets ran his handpicked crew through the preflight procedures. Capt. Parsons, the weaponeer, and 2nd. Lt. Morris Jeppson, his assistant, boarded Enola Gay. Tibbets fired up the engines at 02:00.

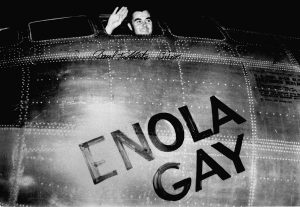

Col. Tibbets wave to the photographer from the Enola Gay cockpit. (Contributed Photo)

The weather aircraft left Runway Able at 02:30. Each was to report actual weather conditions at the proposed targets to Tibbets in Enola Gay. Meanwhile Capt. Chuck McKnight would take the Top Secret to Iwo Jima as the backup aircraft, should the Enola Gay have a mechanical problem en route to Japan. Col. Kirkpatrick had visited Iwo Jima to have a bomb loading pit created off the one runway already prepared for B-29s. He would fly to Iwo Jima in a C-54 with a bomb loading team to stand by, just in case.

Tibbets managed a wave at a cameraman then drove Enola Gay to the west end of Runway Able. Tibbets faced Enola Gay into a light easterly wind. With the checklist completed, Tibbets and his co-pilot, Capt. Robert A. Lewis, pushed the throttles forward to the max, then released the breaks. Overloaded, with two extra crew members, an extra 700 gallon in auxiliary fuel tanks and a 9,500-lb bomb aboard, Enola Gay lumbered down the 8,500-foot runway. The plane had to reach 155 miles per hour to lift off. As the end of the runway approached, Lewis balked and shouted at Tibbets to pull up. Tibbets paid him no attention. Dr. Norman Ramsey was standing near the end of the runway. As Enola Gay passed him, Ramsey saw the big bird’s wheels lift off the ground with bright blue flames flaring out of the engines as Enola Gay fought for altitude and gradually banked to the north. It was 02:45am.

Cruising at 4,700 feet, Capt. Parsons and his assistant climbed into the bomb bay and inserted the explosive charges behind the uranium “bullet” that would slam into the uranium target and spark the nuclear reaction. They flew on toward their rendezvous at Iwo Jima, knowing they had a live atomic bomb on board.

The mushroom cloud after Little Boy exploded over Hiroshima. (Contributed Photo)

The only thing that had been proven at Alamogordo on July 16 was that the new plutonium gadget could explode. The uranium device had never been tested. They didn’t have enough purified Uranium-235 to make one for testing. Dropping Little Boy from 30,000 feet would be just as much an experiment as had been the Trinity Test.

The Great Artist, carrying equipment to measure the strength of the bomb, and Necessary Evil, carrying photo equipment and official observers, joined up with Enola Gay at 06:07 over Iwo Jima and headed to Japan. At 08:30am Tibbets received a message from Eatherly: “Y-3, Q-3, B-2, C-1”, which roughly translated to “skies clear over Hiroshima.” Tibbets’ handpicked navigator, Capt. Theodore “Dutch” Van Kirk, set a course for Hiroshima and his handpicked flight engineer, Tech Sgt. Wyatt E. Duzenbury, put them on the target on time. No fighters. No flak. A “milk run” to Hiroshima.

The Japanese paid no attention to three lone B-29s. They did not go to the air raid shelters. At 09:09am Tibbets turned the plane over to his handpicked bombardier, Maj. Thomas Ferebee, who released the bomb at 09:15:17am. It fell for 43 seconds, which seemed an eternity to Capt. Parsons. Would it go off? Would it turn out to be a dud? Then, Little Boy exploded at about 1,950 feet above Hiroshima with the force of about 15,000 tons of dynamite. A giant radioactive cloud began to rise toward the plane. Tibbets put Enola Gay into a tight, diving 159-degree right turn to escape the bomb blast.

With no damage to the aircraft, Tibbets headed straight for Tinian. There, Gen. Carl Spaatz awaited Enola Gay’s return, pinning the Distinguished Service Medal on Tibbets’ service overalls.

The Project Alberta team turned its attention to Fat Man, the plutonium-based bomb, in Assembly Building No. 3. The plan had been to drop two in succession, a left-right combination to knock out the Japanese.

LeMay received another weather report from China. The weather was turning bad.

Don Farrell (Special to the Saipan Tribune)

Don Farrell is author of the acclaimed book Tinian and The Bomb, available on line at https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07BMTVF1K