July 25, 1945: The decision of the century

This photo shows the three atomic bomb assembly buildings just to the northwest of North Field, the secret 1st Ordnance Area just west of the field, and the atomic bomb loading pits. Photo courtesy Leon Smith, 509th

President Harry Truman was in Potsdam, Germany on July 16, 1945, discussing postwar Europe with Churchill and Stalin. That evening, Secretary of War Henry Stimson walked into Truman’s villa and handed him an encrypted message from Washington, D.C.: “Operated on this morning. Diagnosis not yet complete, but results seem satisfactory and already exceed expectations…”

The Trinity Test of a plutonium-based bomb had been successful. Suddenly, there was an alternative to an invasion of Japan. Nonetheless, the Chiefs of Staff remained vehement that the only certain way to end the war was to invade. The Japanese had fought every battle to the bitter end and, in their opinion, would never surrender until armed Americans entered the Emperor’s palace. Young Americans who had fought in Europe and North Africa were notified they were being rerouted to the Pacific.

To use the bomb, or not to use the bomb. To end the war immediately by using first generation weapons of mass destruction, or clamp down on the blockade of Japan and continue the merciless bombing until the Japanese burn or starve to death. Which would be less inhumane?

The war in Asia was still raging. Some 5,000 Allied men, along with thousands more Japanese and Chinese, were dying daily in rotting jungles between Burma and the Philippines. If he did not use the bomb, what would he tell the mothers of all those young men who died waiting for Japan to surrender?

USS Indianapolis just off Tinian after delivering key components of the Little Boy atom bomb. Photo courtesy Leon Smith.

On July 25, Secretary of War Henry Stimson handed President Truman a copy of the draft order for the use of atom bombs against Japan:

“The 509th Composite Group, 20th Air Force will deliver its first special bomb as soon as weather will permit visual bombing after about 3 August 1945 on one of the targets: Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata and Nagasaki. …Additional bombs will be delivered on the above targets as soon as made ready by the project staff.”

Truman made his decision:

“Suggestion approved.

“Release when ready.

“But not sooner than August 2.”

HST

Truman reserved the right to revoke the order up to the last moment, but the wheels were in motion. Stimson said later that it was their “least abhorrible option.”

On July 26, 1945, Truman, Churchill, and Chiang Kai-shek issued an ultimatum to Japan and broadcast it around the world: “We call upon the Government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all the Japanese armed forces, and to provide proper and adequate assurances of their good faith in such action. The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.”

Note that the message required only the surrender of all the Japanese armed forces, not their emperor.

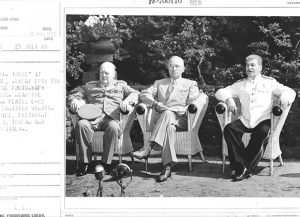

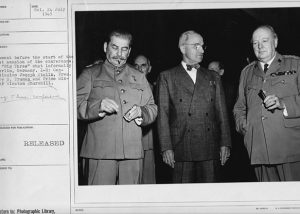

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, U.S. President Harry Truman, and Soviet Union Marshall Joseph Stalin pose for a photo at Potsdam. It is July 25. Truman has made his decision to use the bomb. Photo courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 80.

American radio stations transmitted the message to Japan. On July 27, millions of pamphlets containing excepts from the ultimatum were printed on Saipan and dropped on major Japanese cities from B-29s. Japanese Premier Adm. Kantarō Suzuki responded, referring to the ultimatum as “a rehash of the Cairo Declaration, and the government therefore does not consider it of great importance. We must mokusatsu it (kill it with silence).”

Allied forces were ordered to maintain “unremitting pressure” against Japan. LeMay now announced the names of the cities he would bomb, dropping millions of leaflets stating, “We give the military clique this notification of our plans because we know there is nothing they can do to stop our overwhelming power and our iron determination. We want you to know how powerless the military is to protect you.”

Seen here, from left, are Soviet Union Marshall Joseph Stalin, U.S. President Harry Truman, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill the day before Truman’s decision to use the bombs. Photo courtesy National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 80.

On Aug. 1, Air Force Day, 1945, LeMay sent 800 B-29s from the five bases on Saipan, Tinian and Guam to bomb Japan. They flew with impunity; there was no Japanese defense of any significance. That same day, General Spaatz flew to Manila and handed General MacArthur a copy of the order to drop the bombs, then returned to Guam. He had already given a copy to Nimitz.

Still, no message from Tokyo.

The weather over Japan was looking good for after Aug. 4.

General Carl Spaatz issued the Centerboard order to General LeMay on Guam, who forwarded it to General James Davies, C.O. of the 313th Bomb Wing on Tinian, who issued it to Colonel Paul Tibbets, C.O. of the 509th Bomb Group.

Don Farrel (Special to the Saipan Tribune)

Don Farrell is author of the acclaimed book Tinian and The Bomb, available on line at https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07BMTVF1K