July 16, 1945: The Trinity Test

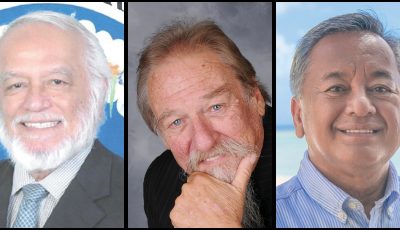

Photo shows the little container holding the plutonium sphere being loaded into the Packard that took it to the Trinity site.

Today, July 16, 2020, is the 75th anniversary of a true turning-point in world history. It is worthy to reflect on what happened then, and how it affected life in the Marianas then and now.

With the war in the Pacific reaching its climax, scientists and military technicians were preparing for a billion-dollar science fair project, codenamed the Trinity Test. Because of its military potential, Major General Leslie Groves, U.S, Army Corps of Engineers, Commanding Officer of the Manhattan Project, was present. No media allowed.

Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Los Alamos Laboratory was on the hot seat. After two years of work, Oppenheimer was preparing to prove that an atom of plutonium could be split in half and in the process spark a nuclear chain reaction, releasing huge amounts of energy. The time had come to put up or shut up.

Oppenheimer’s “gadget” had been assembled at the Los Alamos Laboratories, without the nuclear material, which would be inserted last. This was an implosion-type, plutonium-based device, a totally new scientific creation. Over the last two years, and millions and millions of War Department dollars, scientists and engineers had manufactured sufficient plutonium in top secret nuclear reactors at Hanford, Washington to produce a sphere of it about the size of a softball. With thirty-two concentrically shaped, black-powder charges surrounding it, all designed to explode absolutely simultaneously, the scientists expected to crush the ball of plutonium to about the size of a golf-ball, at which point it would reach critical mass and explode – according their formulae. They would find out, one way or the other, at the Trinity Test.

After one last honing at Los Alamos on July 12, the hemispheres of the plutonium core were placed inside a lead-lined, aluminum bucket, which was carried from the Laboratory to the backseat of a 1945 Packard and driven to a ranch house on the Alamogordo Bombing Range in the Jornado del Muerto desert, “Journey of Death,” New Mexico. At 0900 Friday morning, July 13, the plutonium hemi-spheres and the polonium initiator were properly assembled, and wrapped in a gold foil dampener, and driven further into the desert, arriving at the base of a 200-foot-tall, steel forestry tower. It required two days to properly insert the core into the 7,000-pound gadget, hoist it to the top of the tower, connect all the electrical circuits within the gadget, test them, then connect the gadget to Trinity Base Camp, 10,000 feet away, and test all the circuits again.

It rained on the morning of the 16th. Nobody wanted to play with electricity in the rain. Groves became agitated. The rain gods quieted. Oppenheimer agreed to a 0530 firing. Among the physicists, chemists, mathematicians, and metallurgists watching from 10 miles away, the odds on what would happen were running about even. Predictions varied from a complete fizzle to the destruction of Earth.

The countdown began. Everyone was ordered to lay face down, feet toward the blast. After the blast, they could set up and watch whatever happened through smoked glass.

The gadget being hoisted up the tower.

The clock ticked down. Suddenly, with no sound, matter became energy. The desert lit up, “brighter than a thousand suns,” said one observer. Groves rolled over and looked at the growing mass of brilliant energy being released from that small ball of plutonium. Then came the roar and the wind blast.

Groves, a gruff SOB, was astounded, almost dumbfounded. One of the scientists grinned and said, “The damned thing worked.” Others said something more along the line of, “Oh shit!”

The nuclear era was born.

Groves immediately sent a telex to the No. 2 man in the War Department, who sent the following message to Potsdam, Germany, where President Truman was waiting for the results.

“Operated on this morning. Diagnosis not yet complete, but results seem satisfactory and already exceed expectations.”

Truman smiled, and put it in his pocket.

However, July 16 was far from over. Just hours later that same morning, a large wooden crate weighing about ten tons and marked “Top Secret” was lashed down to the deck of the light cruiser USS Indianapolis at Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, San Francisco. A 300 # lead-lined, aluminum bucket holding about half the uranium necessary for a different kind of atomic bomb (a term not often used since H. G. Wells created it in The World Set Free, 1914), was bolted to the deck of the flag officer’s cabin. One of two couriers from the Manhattan Project would remain with the bucket for the duration of the cruise.

Captain Charles Butler McVay, III, commanding officer of the Indianapolis, received a most extraordinary order with the box and the bucket:

“You will sail at high speed to Tinian where your cargo will be taken off by others. You will not be told what the cargo is, but it is to be guarded even after the life of your vessel. If she goes down, save the cargo at all costs, in a lifeboat if necessary. And every day you save on your voyage will cut the length of the war by just that much.”

The Indianapolis left immediately, sailing under the Golden Gate Bridge, making a bee-line for Tinian, some 5,700 miles west.

In the days after the Trinity Test, scientists and technicians from Los Alamos began flying to Tinian. Colonel Elmer E. Kirkpatrick, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, had arrived at Tinian the end of March and began constructing the facilities the scientists and technicians would need to assemble atomic bombs, as many as necessary to force Japan to surrender. Commander Dick Ashworth, USN, arrived with Dr. Norman Ramsey, to oversee the bomb assembly and delivery, if necessary. On July 25, the order to drop the first bomb was issued. The Indianapolis arrived at Tinian the next day.

Scientists and technicians on Tinian prepared for the next great experiment– could an “atom bomb” be dropped from a B-29 at 30,000 feet and have the same results?

Note: Photos are from Los Alamos Historical Museum through a grant from the Northern Marianas Humanities Council.

Don Farrel (Special to the Saipan Tribune)

Don Farrell is author of the acclaimed book Tinian and The Bomb, available on line at https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07BMTVF1K